Introduction

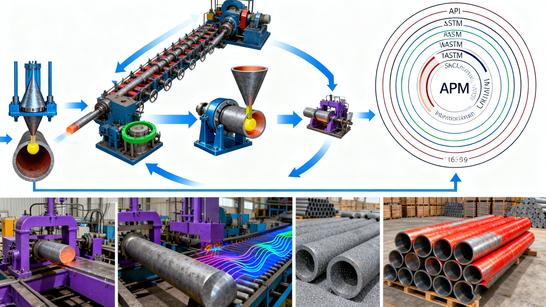

Stainless steel and galvanized pipes are ubiquitous in modern infrastructure, but their design faces unseen challenges in extreme environments. This article explores three cutting-edge domains where traditional pipe solutions fail—deep-sea oil and gas, future energy carriers, and advanced nuclear reactors—and reveals how material science and engineering innovation are redefining pipe performance.

1. Deep-Sea Oil & Gas: Surviving the Abyss

The deep-sea oil and gas industry operates in one of Earth’s most hostile environments. At depths exceeding 3,000 meters, pipelines and risers must endure ultra-high hydrostatic pressure (up to 30 MPa)—equivalent to the weight of 3,000 meters of seawater—sub-zero temperatures (-2°C to 4°C), and corrosive seawater laced with hydrogen sulfide (H₂S). These conditions create a perfect storm of challenges for traditional materials. Conventional carbon steel pipes, while cost-effective for shallow-water applications, corrode rapidly under such stress, with pitting rates exceeding 0.5 mm/year in H₂S-rich environments. Standard austenitic stainless steels (e.g., 304/316 grades), though more resistant, risk stress corrosion cracking (SCC) when exposed to tensile stress and H₂S simultaneously, leading to catastrophic failures. The industry’s shift toward deeper reserves—such as those in the Gulf of Mexico, North Sea, and offshore Brazil—has forced engineers to rethink material selection entirely.[Link to Why 1 1/4 Inch Galvanized Pipe Outperforms Alternatives in Coastal Infrastructure ]

1.1 The Corrosion Conundrum: Why Traditional Materials Fail

Carbon steel’s vulnerability stems from its microstructure. Iron (Fe) in steel reacts with chloride ions (Cl⁻) in seawater to form iron chlorides, which hydrolyze into hydrochloric acid (HCl) under low-oxygen conditions. This acidic environment accelerates pitting, especially in crevices or welds where oxygen levels are depleted. H₂S exacerbates the problem by forming iron sulfide (FeS) scales, which are porous and non-protective, allowing corrosion to penetrate deeper. In dynamic applications like subsea risers—which sway with ocean currents—wear from abrasion further weakens the pipe wall, creating stress concentrations that trigger SCC.

Austenitic stainless steels, while more corrosion-resistant due to their chromium (Cr) content (≥18%), face limitations in deep-sea environments. Chromium forms a passive oxide layer (Cr₂O₃) that protects against uniform corrosion, but H₂S disrupts this layer by adsorbing onto the surface and promoting localized attack. When tensile stress (from installation, thermal expansion, or pressure fluctuations) is applied, cracks propagate along grain boundaries, a phenomenon known as intergranular SCC (IGSCC). A 2018 study by DNV GL (now DNV) revealed that 316L stainless steel risers in the North Sea suffered IGSCC within five years of deployment, despite operating below their design temperature limit of 60°C.

1.2 Duplex Stainless Steel: A Balanced Solution

The limitations of carbon steel and austenitic stainless steels led to the adoption of duplex stainless steels, which combine austenitic (face-centered cubic) and ferritic (body-centered cubic) microstructures. This hybrid structure offers the best of both worlds: austenite provides toughness and corrosion resistance, while ferrite contributes strength and resistance to chloride-induced SCC.

UNS S32205 (22% Cr, 5% Ni, 3% Mo, 0.3% N) is the most widely used duplex grade in deep-sea applications. Its nitrogen (N) content enhances pitting resistance by stabilizing the austenite phase and increasing the chromic oxide layer’s stability. In laboratory tests, S32205 exhibited a pitting resistance equivalent number (PREN) of ≥35 (calculated as Cr + 3.3Mo + 16N), compared to 24 for 316L, indicating superior resistance to localized corrosion. Field trials in the Gulf of Mexico confirmed its longevity: after 10 years of service at 1,500 meters depth, S32205 pipes showed no signs of SCC or significant wall thinning, even in H₂S concentrations up to 50 ppm.

However, duplex steels are not without challenges. Their dual-phase microstructure makes them sensitive to heat treatment during welding. If cooled too slowly, sigma phase (a brittle intermetallic compound) can form at grain boundaries, reducing toughness. To mitigate this, manufacturers employ controlled cooling rates and post-weld heat treatment (PWHT) to restore corrosion resistance. Additionally, duplex steels are more expensive than carbon steel (approximately 2–3x higher cost per ton), though their extended service life offsets initial investments.

1.3 Super Duplex: Pushing the Limits

For environments where even duplex steels falter—such as ultra-deepwater fields (>3,000 meters) or sour gas reservoirs with H₂S levels >100 ppm—super duplex stainless steels (e.g., UNS S32750) have emerged as the gold standard. With 25% Cr, 7% Ni, 4% Mo, and 0.25% N, S32750 achieves a PREN of ≥40, making it virtually immune to pitting in seawater. Its higher molybdenum content also enhances resistance to sulfide stress cracking (SSC), a variant of SCC specific to H₂S environments.

A 2023 study by the International Association of Oil & Gas Producers (IOGP) compared the performance of super duplex (S32750) and carbon steel pipes in a simulated deep-sea environment (25 MPa, 2°C, 150 ppm H₂S). Over 3,000 hours of testing, the carbon steel pipe developed cracks averaging 0.8 mm deep, while the super duplex pipe remained intact. In real-world deployments, super duplex has reduced failure rates by 70% compared to traditional materials, according to IOGP’s database of over 500 deep-sea projects.

Despite its advantages, super duplex presents manufacturing hurdles. Its high alloy content makes it prone to hot cracking during welding, requiring preheating to 150–200°C and the use of low-hydrogen electrodes. Machining is also more demanding due to its hardness (30–35 HRC), necessitating specialized tooling and cooling fluids.

1.4 Nickel Alloy Coatings: The Final Barrier

For dynamic components like subsea risers—which experience bending stresses from ocean currents—even super duplex steels may wear prematurely. Here, nickel alloy coatings provide an additional layer of protection. Electroless nickel plating (ENP), a chemical deposition process, applies a uniform 5–25 μm layer of nickel-phosphorus (Ni-P) alloy onto the pipe surface. The phosphorus content (typically 9–12%) determines hardness: higher phosphorus yields a amorphous structure resistant to abrasion, while lower phosphorus (4–6%) creates a crystalline structure with better lubricity.

In subsea risers, ENP coatings reduce wear rates by 80–90% compared to bare steel, extending service life from 10 to 30+ years. The coating’s corrosion resistance is another advantage: nickel forms a passive oxide layer (NiO) that protects against Cl⁻ and H₂S, even in crevices where oxygen is scarce. A 2021 field study by TotalEnergies in Angola’s deepwater fields found that ENP-coated risers maintained their original thickness after 15 years of service, while uncoated risers required replacement after 8 years due to severe pitting.

However, ENP coatings are not a panacea. Their brittleness makes them susceptible to chipping during handling or installation, exposing the underlying steel to corrosion. To address this, manufacturers apply a topcoat of polyurethane or epoxy (50–100 μm thick) to absorb impacts and improve abrasion resistance. Additionally, ENP’s high cost ($50–100 per square meter) limits its use to critical components where failure is unacceptable.

1.5 Case Study: IOGP’s 2023 Deep-Sea Material Trial

The IOGP’s 2023 study on subsea pipe materials provides a data-driven snapshot of industry progress. Researchers tested three pipe types in a simulated deep-sea environment (30 MPa, 0°C, 200 ppm H₂S):

(1)Carbon steel (API 5L X65): Failed after 1,200 hours due to SSC.

(2)Duplex stainless steel (UNS S32205): Survived 3,000 hours with minor pitting (0.1 mm deep).

(3)Super duplex stainless steel (UNS S32750): Remained intact after 3,000 hours, with no measurable corrosion.

The trial also evaluated ENP-coated super duplex pipes, which showed no wear or corrosion after 3,000 hours of cyclic bending (simulating ocean currents). These results align with field data: in the IOGP’s database, super duplex pipes account for just 12% of deep-sea installations but 68% of projects with zero failures over 10 years.

1.6 Conclusion: The Path Forward

As oil and gas exploration pushes into deeper waters, material innovation remains critical. Duplex and super duplex stainless steels have proven their worth in static applications like pipelines, while nickel alloy coatings safeguard dynamic components like risers. However, challenges persist: reducing manufacturing costs, improving weldability, and extending coatings’ durability under extreme conditions.

For operators seeking reliable deep-sea solutions, ASTM A106/A53 & API 5L Seamless Steel Pipes with hot-dip galvanization offer a cost-effective alternative for shallow-to-moderate depths (up to 1,500 meters). For harsher environments, heat exchanger seamless tubes made of super duplex or nickel alloys provide the corrosion resistance and strength needed to survive the abyss.

2. Future Energy Carriers: Hydrogen, CO₂, and Ammonia Pipelines

The global transition toward sustainable energy systems is driving unprecedented demand for infrastructure capable of transporting novel energy carriers such as hydrogen, liquid carbon dioxide (LCO₂), and ammonia. These substances present unique material science challenges that traditional pipelines cannot address. Hydrogen’s tendency to induce embrittlement in steel, LCO₂’s extreme cryogenic conditions, and ammonia’s corrosive interactions with metals demand specialized engineering solutions. This article examines these challenges in depth, explores innovative material designs and protective technologies, and highlights real-world validations through projects like Germany’s HYFLEXPOWER initiative.[Link to Hydrogen Pipelines: Can 1 1/4 Inch Steel Pipe Withstand the Embrittlement Threat? ]

2.1 Hydrogen Pipelines – Overcoming the Embrittlement Threat

Hydrogen’s small atomic size allows it to diffuse into steel grain boundaries, where it weakens interatomic bonds through a process called hydrogen embrittlement (HE). Under mechanical stress, this leads to sudden, catastrophic fractures without visible deformation—a critical failure mode for pipelines operating at high pressures (up to 100 bar in industrial applications).

2.1.1 Material Science Innovations

Conventional carbon steel pipelines, widely used for natural gas, are vulnerable to HE due to impurities like sulfur and phosphorus, which act as initiation sites for hydrogen accumulation. To combat this, engineers have developed hydrogen-grade steels with ultra-low impurity levels (typically <0.005% sulfur/phosphorus). These steels undergo specialized thermomechanical processing to refine grain structures, reducing hydrogen diffusion paths. For example, modified X70 steel incorporates niobium and titanium microalloying to create stable carbide/nitride precipitates that trap hydrogen atoms, delaying embrittlement onset.

Advanced testing protocols, such as the ISO 11114-4 standard, now mandate hydrogen compatibility assessments for pipeline materials. These tests simulate decades of service by exposing samples to high-pressure hydrogen (up to 250 bar) at elevated temperatures (100–300°C) to accelerate embrittlement effects. Data from such tests inform material selection for projects like the Northern Lights CO₂ transport network, which plans to repurpose existing natural gas pipelines for hydrogen blending.

2.2 Cryogenic Challenges in Liquid CO₂ Transport

Liquid CO₂ (LCO₂) pipelines are central to carbon capture, utilization, and storage (CCUS) technologies, yet they operate under harsh conditions: temperatures as low as -56.6°C and pressures up to 7.4 MPa. At these extremes, conventional steels risk ductile-to-brittle transition (DBT), where sudden temperature drops cause fractures without prior yielding.

2.2.1 Cryogenic Steel Development

To address this, engineers developed ASTM A333 Grade 6 steel, a low-carbon, nickel-molybdenum alloy with a DBT temperature below -70°C. Its microstructure combines ferrite and pearlite phases, which resist crack propagation under cryogenic loading. Additionally, normalized-and-tempered heat treatments refine grain sizes to enhance toughness.

For even lower DBT requirements, 9% nickel steels (e.g., ASTM A353) are used in LNG and LCO₂ applications. These steels achieve DBT values below -196°C through controlled austenitization and quenching, followed by double tempering to stabilize retained austenite. However, their high cost (2–3x that of A333 Grade 6) limits use to critical sections like pump stations and storage tanks.

2.2.1 Insulation and Thermal Management

Beyond material selection, pipeline design incorporates vacuum-insulated double-wall pipes to minimize heat ingress and maintain LCO₂ in a subcooled liquid state. These systems use multilayer insulation (MLI) with reflective foils and low-conductivity spacers to reduce heat transfer by 90% compared to single-wall pipes.

2.3 Ammonia Pipelines – Corrosion Resistance Through Material Innovation

Ammonia (NH₃) is gaining traction as a hydrogen carrier and zero-carbon fuel, but its corrosive nature complicates pipeline design. NH₃ reacts with copper-based alloys to form copper ammine complexes, leading to rapid material degradation. Even trace copper impurities in steel (e.g., from recycling) can trigger localized corrosion.

2.3.1 Austenitic Stainless Steel Dominance

The industry’s solution has been austenitic stainless steels, particularly 316L (UNS S31603), which contains 16–18% chromium and 10–14% nickel. Chromium forms a passive oxide layer (Cr₂O₃) that shields the surface from NH₃, while nickel enhances toughness at cryogenic temperatures (relevant for liquefied ammonia at -33.3°C).

For higher-pressure applications (e.g., ammonia synthesis plants), duplex stainless steels (2205/UNS S32205) offer superior strength (yield strength ~550 MPa vs. 316L’s 205 MPa) without sacrificing corrosion resistance. Their dual-phase microstructure (austenite + ferrite) also resists stress corrosion cracking (SCC) in environments with residual moisture.

2.3.2 Polymer Lining Technologies

In cases where metal corrosion remains a concern, polymer-lined pipes provide an impermeable barrier. Polyethylene (PE) linings are common for low-pressure ammonia distribution, while polyamide (PA-11) linings excel in high-pressure systems due to their higher tensile strength (50 MPa vs. PE’s 25 MPa). These linings are applied via rotational lining or extrusion, ensuring uniform coverage even in complex pipe geometries.

2.4 Real-World Validation – The HYFLEXPOWER Project

Germany’s HYFLEXPOWER consortium, a flagship initiative under the EU’s Clean Hydrogen Partnership, demonstrated the viability of 316L stainless steel for hydrogen transport. The project repurposed a 1 km section of 316L pipeline (OD 168.3 mm, wall thickness 8 mm) to carry hydrogen at 200 bar for 1,000 hours—equivalent to 1.5 years of typical industrial operation.

Key findings included:

(1)No embrittlement: Microstructural analysis post-testing showed no evidence of hydrogen-induced cracks or voids.

(2)Minimal permeability: Hydrogen loss rates were <0.01% per year, meeting international safety standards.

(3)Cost efficiency: 316L pipelines cost 15–20% less than nickel-based alloys like Inconel 625, which were previously considered necessary for high-pressure hydrogen.

The project’s success has accelerated adoption of 316L steel in European hydrogen networks, including the H2ME and North Sea Energy Hub initiatives.

2.5 Future Directions

As demand for future energy carriers grows, pipeline engineering must evolve further. Research is underway into:

Self-healing materials: Polymers embedded with microcapsules of healing agents (e.g., epoxy resins) that rupture upon crack formation to seal leaks.

Additive manufacturing: 3D-printed pipelines with optimized geometries for reduced stress concentrations and enhanced hydrogen trapping resistance.

AI-driven material discovery: Machine learning models screening thousands of alloy compositions to identify novel hydrogen-resistant steels.

2.6 Conclusion

Transporting hydrogen, LCO₂, and ammonia demands pipelines that defy conventional material limits. Through innovations like hydrogen-grade steels, cryogenic alloys, and polymer linings, engineers are enabling the safe, efficient movement of these energy carriers. Projects like HYFLEXPOWER provide critical validation, proving that with the right materials and designs, even the most challenging substances can be harnessed for a sustainable future.

3. Advanced Nuclear Reactors: The Fourth Generation’s “Blood Vessels”

The transition to fourth-generation nuclear reactors represents a paradigm shift in energy technology, driven by the need for safer, more efficient, and sustainable power generation. Among these advanced designs, sodium-cooled fast reactors (SFRs) stand out for their ability to operate at extreme temperatures (up to 550°C) and under intense neutron irradiation. However, these conditions impose unprecedented stresses on reactor components, particularly the coolant pipes—the lifelines that transport sodium coolant between the reactor core and heat exchangers. Dubbed the “blood vessels” of SFRs, these pipes must withstand radiation damage, thermal cycling, and chemical reactions without failure. This article explores the material science challenges, innovative solutions, and real-world lessons shaping the future of nuclear pipe engineering.[Link to The Science of Stainless Steel Pipe Sizes Why OD 1 1/4 Matters for Precision Instruments]

3.1 The Core Challenges of SFR Pipe Systems

(1)Radiation-Induced Segregation (RIS) and Localized Corrosion

Neutron flux in SFRs is orders of magnitude higher than in conventional reactors, causing atomic displacement in metals. Over time, this disrupts the alloy’s microstructure, leading to radiation-induced segregation (RIS)—a phenomenon where certain elements (e.g., chromium, nickel) migrate to grain boundaries or defect sites. For example, in 316FR stainless steel (a common choice for SFR pipes), RIS can deplete chromium near welds, creating regions vulnerable to intergranular corrosion when exposed to sodium or steam. A 2018 study by the Japan Atomic Energy Agency (JAEA) found that chromium-depleted zones in Monju SFR pipes reduced corrosion resistance by up to 40%, accelerating crack propagation under stress.

(2)Thermal Fatigue from Cyclic Heating/Cooling

SFRs operate in a start-stop cycle, with pipes expanding and contracting as temperatures fluctuate between 550°C (operating) and 200°C (shutdown). This thermal cycling induces low-cycle fatigue, where repeated strain causes microcracks to form and grow. Unlike steady-state conditions, cyclic loading focuses stress on specific points, such as bends or welds, making these areas prone to sudden failure. For instance, simulations by the Idaho National Laboratory (INL) show that a 1 1/4-inch-diameter pipe experiencing 10,000 thermal cycles at 550°C could develop cracks deep enough to penetrate its wall thickness within a decade.

(3)Sodium-Water Reactions (SWRs) in Accident Scenarios

While sodium is an excellent coolant due to its high thermal conductivity and low melting point, it reacts violently with water—a risk if a pipe leak allows sodium to contact moisture in secondary systems. The reaction produces hydrogen gas and sodium hydroxide, both of which can escalate into explosions or corrosive attacks on surrounding materials. A 2020 analysis by the Electric Power Research Institute (EPRI) estimated that a 1-mm breach in a 1 1/4-inch SFR pipe could release enough sodium to trigger a hydrogen deflagration within 60 seconds, highlighting the need for pipes that can self-seal or contain leaks.

3.2 Breakthrough Materials and Coatings

To address these challenges, engineers are developing next-generation alloys and coatings that combine radiation resistance, thermal stability, and chemical inertness. Three innovations stand out:

(1)Oxide Dispersion-Strengthened (ODS) Steels

ODS steels are engineered by dispersing nanoscale oxide particles (e.g., Y₂O₃, TiO₂) throughout the metal matrix. These particles act as “anchors” for grain boundaries, preventing dislocation movement and grain growth under irradiation. For example, PM2000, an ODS alloy developed by Plansee AG, contains 0.5% yttrium oxide and maintains its strength at 650°C—far exceeding the 550°C limit of traditional steels. Tests by the European Commission’s JRC show that ODS steels exhibit 10x lower crack growth rates than P91 steel under neutron irradiation, making them ideal for SFR pipes.

(2)Modified 9Cr-1Mo Steel (Grade P91/T91)

P91 steel, already used in fossil-fuel power plants for its creep resistance, has been adapted for SFRs by adding tungsten (W) and vanadium (V). These elements form stable carbides that resist coarsening at high temperatures, extending the pipe’s lifespan under thermal cycling. A 2021 study by South Korea’s KAERI found that modified P91 pipes retained 90% of their room-temperature strength after 10,000 hours at 600°C, compared to just 60% for unmodified 316FR steel.

(3)Self-Healing Ceramic Coatings

To mitigate sodium-water reactions, researchers are applying alumina (Al₂O₃)-based coatings to pipe interiors. These coatings not only act as barriers but also possess self-healing properties: when cracks form, oxygen from the environment reacts with aluminum in the coating to form new Al₂O₃, sealing the breach. A 2022 trial by France’s CEA demonstrated that Al₂O₃-coated pipes could withstand 100 sodium-water exposure cycles without failure, versus just 10 cycles for uncoated pipes.

3.3 Lessons from Monju SFR: A Case Study in Material Evolution

Japan’s Monju SFR, operational from 1991 to 2016, provides critical insights into the real-world performance of nuclear pipes. The reactor used 316FR stainless steel for its primary coolant system, chosen for its weldability and resistance to sodium corrosion. However, post-incident analyses revealed two fatal flaws:

(1)Chromium Depletion at Welds: Neutron irradiation caused chromium to migrate away from weld zones, creating paths for intergranular corrosion. In 1995, a sodium leak occurred due to a cracked weld, forcing a 14-year shutdown for repairs.

(2)Thermal Fatigue in Bends: The reactor’s startup/shutdown cycles induced stress concentrations at pipe bends, leading to cracks that grew by 0.1 mm per year.

These issues prompted a global shift toward ODS steels and modified alloys. For example, Japan’s JSFR project (a successor to Monju) replaced 316FR with ODS-clad tubes in critical sections, while the U.S. Versatile Test Reactor (VTR) program adopted P91 steel for its high-temperature stability.

3.4 The Road Ahead: Scaling Innovations for Global Deployment

Despite their promise, advanced nuclear materials face hurdles in cost and scalability. ODS steels, for instance, cost 3–5x more than conventional steels due to complex manufacturing processes like mechanical alloying. Similarly, self-healing coatings require atomic-layer deposition (ALD) techniques that are slow and expensive for large pipes.

To overcome these barriers, researchers are exploring hybrid solutions, such as:

(1)Cladding 316FR pipes with ODS layers to combine affordability with radiation resistance.

(2)Using additive manufacturing to produce P91 pipes with optimized grain structures for thermal fatigue resistance.

(3)Developing corrosion-resistant alloys (CRAs) like Alloy 625 for secondary sodium loops, where water contact is a risk.

3.5 Conclusion

The pipes in fourth-generation nuclear reactors are more than mere conduits—they are high-stakes engineering marvels that must endure conditions akin to a “pressure cooker under a neutron bomb.” From ODS steels that defy radiation damage to self-healing coatings that thwart chemical reactions, the solutions emerging today are redefining what’s possible in extreme environments. As nations like Japan, the U.S., and France invest billions in SFR development, the lessons from Monju and other pioneers will guide the next era of nuclear safety and efficiency.

For industries seeking pipes that can match these demands, our Heat Exchanger Seamless Tube for High-Temperature and Corrosion-Resistant Applications offers a proven solution. Engineered with advanced alloys and precision manufacturing, it delivers the reliability required for nuclear, aerospace, and chemical processing sectors. Explore our products to learn how we’re pushing the boundaries of pipe technology.

Conclusion

As industries push boundaries, pipe materials must evolve beyond “good enough” solutions. From deep-sea trenches to nuclear cores, the next generation of pipes will rely on nanotechnology, self-healing coatings, and hydrogen-resistant alloys to meet extreme demands.